A Bit About Soviet ZX Spectrum Clones

Also available in: Русский

Around Christmas 2024, my partner received a re-released computer — the Sinclair ZX Spectrum — as a gift from his father.

I grew up in Minsk, and I had never seen a computer like this before. For a few days, we were completely pulled into nostalgia for the 1980s: we played the built-in games, wrote tiny programs in BASIC, and felt like people who were just about to invent the future — but first, a FOR I=1 TO 10 loop.

As it turned out, the new version looks exactly like the old computer with its rubber keyboard, but it comes with more modern specifications and ports (HDMI, USB, etc.). For example, you can load your own games onto it via a USB flash drive — a technology whose existence, it seems, even the boldest science fiction writers of the 1980s had not yet imagined.

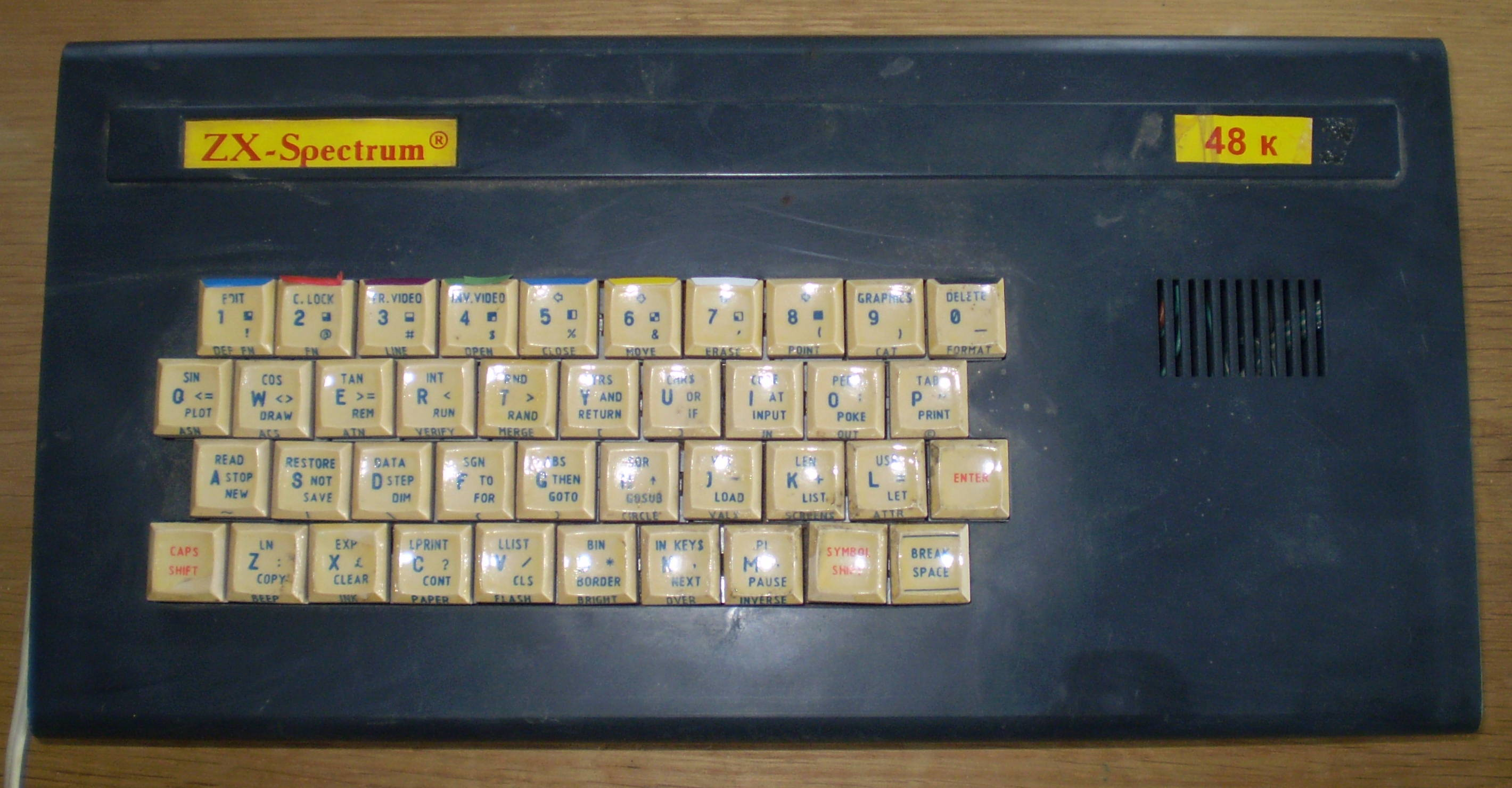

The original Sinclair ZX Spectrum 48K home computer, 1982

Knowing that my own father is a big computer enthusiast, I decided to get him the same kind of gift for the upcoming New Year.

I discovered that, as it turns out, this re-launched Spectrum is not available for purchase in all European countries — so I ordered it from Portugal. The European Union, free movement of goods, and all that — but with caveats.

The great return of The Spectrum, personal archive

I might write more about this particular computer in detail later.

Meeting the clones

A few months later, my friends and I found ourselves at a video game museum in Málaga. Before getting completely absorbed by arcade machines and losing all sense of time, we noticed a large shelf filled with old home computers. Right in the center, like an honorary exhibit, stood a Sinclair ZX Spectrum — with a photograph of its inventor, Clive Sinclair, looking at all this with an expression that said, “I knew this would happen.”

The unmistakable original and Clive Sinclair, video game museum in Málaga, personal archive

That was when I noticed something even more interesting: dozens of keyboards on nearby shelves that looked exactly like Spectrums, but with Cyrillic stickers on the keys.

One of them was called “Robik” (Arithmetic-Logic Unit “Robik”):

Robik, Ukraine, 1989–1994, video game museum in Málaga, personal archive

Another one was called “Kvant”:

Kvant, Belarus, 1993, video game museum in Málaga, personal archive

All this variety of Cyrillic keyboards awakened my research curiosity. I knew that in the Soviet Union it was popular to build computers from magazine schematics, copying Western machines. But I had underestimated the scale. As it turned out, more ZX Spectrum clones were built in the USSR than in the rest of the world combined. Enthusiasts enthusiastically reverse-engineered Spectrums that had somehow made their way across borders, customs, and probably fate itself.

Since the Spectrum was cheaper and simpler than, say, an IBM computer, it was easier to copy.

Before long, dozens of unofficial Spectrums spread across the Soviet bloc. Oh boy have I realized that moment this story was not going to let me go so easily.

Clone wars

In Soviet times, using Western computers was difficult, expensive, and mildly adventurous. The Speccy was born in Britain in the 1980s. There were no formal restrictions on importing it into the USSR, but its price was around 1,700 rubles — roughly the annual salary of an average engineer. So buying the original was not an option (as with many other things in the USSR).

The alternative — “what if we just make one ourselves?” — looked far more realistic. The Spectrum was a natural target for cloning: its design was simple enough that local factories, cooperatives, or just very motivated individuals could reproduce it. Some people bought original machines “through connections,” then painstakingly disassembled them and copied the circuit boards layer by layer. There were even attempts to copy photomasks (silicon “imprints”) of Western processors or graphics chips — it sounds like a spy thriller, but with a soldering iron. Some Soviet Z80 clones were literally made using such photomasks.

It’s no surprise that this involved months of trial and error — and possibly some quiet engineering tears.

Practically speaking, we can identify several waves of Spectrum cloning in the USSR.

First wave: DIY (1985–1988)

The first wave of late-1980s clones consisted of nearly complete copies of the original Spectrum 48K — sometimes with a slightly improved keyboard, sometimes simply with the hope that “this will do.”

For the most part, these computers were assembled by hobbyists at home, in kitchens, and in radio engineering clubs. The main sources of knowledge were magazines like Radio or Technology for Youth, where schematics were printed as if the reader was expected to understand everything at a glance.

Leningrad-1 (1987–1988) was one of the first clones with a documented design that spread widely among radio engineering enthusiasts. Its creator, Sergey Zonov, used a minimal set of components (around 50 chips) to recreate the Spectrum 48K in Soviet conditions. He effectively set the tone for all future copies in the USSR (cheap, it works, we’ll figure out the rest later).

Second wave: local production and clones of clones (1988–1992)

Pretty quickly, the DIY approach evolved into something more industrial. Clones began to be produced by cooperatives and small factories. For example, the Belarusian Baltic, first released in 1988 by the “Sonet” factory in Minsk, was a computer that looked like a product of a serious enterprise — even if it still carried the spirit of a radio hobby club inside.

Baltic (Sonet), Belarus, 1988, Wikipedia

Another Belarusian machine was the Byte, produced in Brest from 1989 to 1995 — essentially a Spectrum with a Russian-made version of the Zilog Z80 processor.

Byte, Belarus, 1990, Wikipedia

The Ukrainian Robik (shown above, 1989–1998) was another popular Spectrum clone — around 70,000 units were produced, which for that time was almost a startup success story.

These early clones typically had 48 KB of RAM and could run BASIC, just like Sir Sinclair’s original. Many of them also — unexpectedly — supported Cyrillic. Being able to write programs in one’s native language felt like a small but very important form of technological sovereignty.

Over time, improvements appeared: keyboards became more comfortable, joystick support was added, SECAM video output and localized ROMs became available. Some models were clones of other clones — for example, Composite, which grew out of Leningrad-2. A real ecosystem was forming, where the original had long since been lost somewhere in the roots.

Third wave: enhanced clones (1991–1995)

In the early 1990s, while the Soviet Union was falling apart and reality was updating without patch notes, Soviet computer building unexpectedly reached its peak. Enthusiasts added more memory, disk drives, faster processors, and put everything into beige cases so the computer would look “grown-up.” Some clones had up to 4 MB of memory, floppy drives, hard drives, and even modems. You could run various operating systems on them, and overall they looked less and less like the original Spectrum — but they still spoke the same language.

This was practical: an expensive IBM clone at work, a cheap Spectrum at home. Thanks to this, many families got a computer for the first time, and local studios were able to produce games, demos, and software for a very much alive platform (but that’s a whole other story).

The keyboard deserves special mention. The original British Speccy was famous for its rubber keyboard, and many Soviet engineers took this as a personal challenge. For example, the Belarusian Kvant had a full-size 40-key keyboard — no compromises, and with a clear desire to “do it properly.” Kvant, by the way, was one of the last clones of the Soviet era. The USSR no longer existed, but computers were still being produced by inertia.

Here are some examples of “superclones”:

- Pentagon 128 — probably the most famous late clone. It added 128 KB of RAM, a disk interface, and more stable synchronization, becoming the de facto standard for the demoscene in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.

- Scorpion ZS-256 — a high-performance model with 256 KB of RAM, TR-DOS support, and expansion ports for modems and hard drives.

- ATM Turbo — a heavily modified computer with extended graphics modes, up to 4 MB of RAM, and support for custom operating systems.

Looking at all this, it’s hard not to be amazed by how creative people were. Every factory or cooperative added its own little twist (Nafanya was packed into a suitcase!). But in the end, they all spoke the same ZX Spectrum language. That meant all software — games, educational programs, BASIC code listings — usually ran on many different clones.

What happened next?

The Spectrum didn’t go anywhere.

After the collapse of the USSR, clones continued to gather dust and keep working in homes and schools well into the late 1990s. Throwing them away felt wrong, fixing them was hard — but what if you might need it someday? In Western Europe, meanwhile, the Spectrum community gradually migrated online, keeping the platform alive through emulators, homebrew games, and additional hardware.

Today, the future of the Spectrum has calmly split into several parallel realities: retro hardware, the DIY scene, and museum culture — all existing at the same time, and seemingly quite content with this arrangement.

1. The retro hardware revival

Modern reinterpretations — such as the updated Spectrum we played with last Christmas — evoke nostalgia while also attracting proponents of “slow computing.” These are people who consciously choose limitations, because infinite possibilities can be slightly exhausting.

These devices feel like 1980s hardware but behave like neat modern consoles. They allow for more mindful programming and gaming — and provide a rare sense today that you understand the computer as a whole, not just its settings.

2. Active DIY development

In Eastern Europe, new demos, games, and hardware upgrades continue to appear every year. Pentagon and Scorpion clones are still popular, and the scene lives its own somewhat stubborn life — without marketing, but with enormous enthusiasm.

Building, refining, optimizing, and proving (first and foremost to yourself) that it’s possible is a pleasure in its own right. For example: Pikabu

3. Software preservation and museum culture

In video game and computing museums (for example, in Málaga), Spectrums and their clones have taken an honorable place as part of computing history — not glossy, but working. At the same time, many open-source projects are dedicated to scanning magazines, dumping ROMs, and preserving late-Soviet “folk engineering” before it completely dissolves into time.

And yes, if you really want to, you can still find a “someone’s beloved” unit on eBay — for a not exactly cheap price of around $140. History, as we know, tends to appreciate.

Conclusion

When I bought the rebooted Spectrum for my father, I thought it would be just a fun retro gift. Instead, I fell down a rabbit hole into a strange and wonderful world of Soviet computer DIY — a world I had grown up around without really noticing it.

The Cyrillic keyboards in the Málaga museum suddenly made the Spectrum feel like part of my own story. It was no longer an abstract British computer from the 1980s, but a machine that thousands of people in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine built with their own hands: soldering at kitchen tables, repairing with whatever they could get, and using it for programming long before personal computers became commonplace.

I should say that when I first started researching the history of the ZX Spectrum, I mostly looked for material in English — and by doing so, cut myself off from a huge Russian-language layer of content. Once I started searching in Russian, I discovered detailed articles about building clones, photos of circuit boards, stories from developers, and, of course, the history of games — for example, this excellent article. I highly recommend it if this topic became even slightly interesting to you after reading my piece.

Clearly, this history is vast and multi-layered, and it’s impossible to fit it all into a single text. But if I managed to clear away a bit of the fog of war and spark some curiosity to dig deeper — then it was worth it. And if I got something wrong or passed something along through a game of telephone, please don’t be upset — write me a letter by carrier pigeon (or email). I’ll fix it, I promise.

Sources and acknowledgements

Huge thanks to all the articles, archives, and people thanks to whom this history has survived at all:

- https://mysku.club/blog/russia-stores/61156.html — an excellent article on Soviet ZX Spectrum clones with many additional details (ru)

- https://zxbyte.ru - for the information on various ZX Spectrum clone models (ru). Highly recommend!

- https://forum.vcfed.org/ — Vintage Computing Federation (en)

- https://retrocomputing.stackexchange.com/ — Retrocomputing Stackexchange (en)

- https://oldcomputermuseum.com and https://notebook.zoeblade.com — for systematizing hard-to-find information

- The retro enthusiasts maintaining archives of Pentagon, Scorpion, and ATM Turbo

- The Málaga Video Game Museum — for carefully preserved exhibits and inspiration https://oxomuseomalaga.com/en/

- And of course, my father Yegor and my partner’s father Henri — for reminding me that curiosity lives outside of time

P.S.

When I talked to my engineer father from Belarus about this topic, he said that he had never really heard of the Spectrum before and hadn’t seen it or its clones — except maybe briefly in radio engineering circles. What was truly popular in the 1980s were programmable calculators.

So it’s quite possible that the whole ZX Spectrum story remained niche — existing somewhere parallel to the Soviet mainstream. And perhaps that’s exactly why it feels so alive today.